Vancouver’s picturesque coastline is renowned for its thriving aquaculture. With its idyllic climate, gentle sunny days, crystal-clear waters, and serene bays, the city rests gracefully on the banks of the Fraser River. Vancouver waters are home to three primary aquatic treasures: salmon, shellfish, and sea plants, all highly sought after in marine cuisine.

However, in Vancouver, seafood is much more than just a culinary delight; it represents a vital industry with significant social and economic benefits. Experts in the field practice sustainable fishing methods, ensuring the preservation of marine resources and maintaining healthy fish stocks. Vancouverites are committed to resource conservation through responsible fishing and seafood supply practices. Let’s explore the fishing industry in this remarkable city. Next on vancouver-name.

Fishing: An Integral Part of Vancouver’s Life

In Vancouver, the preparation and packaging of seafood are central to the fishing industry. Licensing, inspections, and data collection are critical components of the sector, reflecting the meticulous work involved.

In June 2018, the Wild Salmon Advisory Council (WSAC) was established to help restore salmon populations in British Columbia. This cooperative effort involves collaboration with the public to provide strategic recommendations to provincial authorities. In August 2020, new measures were introduced to implement WSAC’s recommendations, highlighting a deep commitment to improving marine and river ecosystems.

Fishing has always been at the heart of life in Vancouver and British Columbia. Thanks to the region’s natural abundance and proximity to salmon spawning grounds, the Coast Salish First Nations have sustainably utilized these resources for centuries. In the 1800s, coastal settlements grew, and immigrants from Japan, China, and Europe joined the First Nations in fishing and fish processing. The establishment of canneries soon followed, becoming a cornerstone of this culturally rich industry.

The Gulf of Georgia Cannery and Immigrants

The Gulf of Georgia Cannery in Steveston, a district of Richmond in Metro Vancouver, opened in 1894 and remained the province’s largest cannery for nearly a decade. Known as the “Monster Cannery,” it produced millions of cans of salmon annually and required a substantial workforce. Initially, this workforce consisted of First Nations people and Chinese laborers who had completed work on the Canadian Pacific Railway.

As the industry grew, British Columbia’s fishing sector became a beacon of opportunity for workers worldwide. Japanese fishermen played a significant role in the Fraser River fishery, joining First Nations fishers. The first Japanese settler arrived in Steveston in 1887, inspiring many others from Wakayama, Japan, to migrate and work in salmon fishing. Steveston’s Kuno Garden, located in Garry Point Park, is dedicated to Gihei Kuno, a pioneer who encouraged this migration.

European immigrants, including Norwegians, Swedes, Italians, and Greeks, also thrived in the fishing industry. Finnish immigrants settled near Steveston in the 1890s, creating the fishing village of Finn Slough by the 1910s. Today, Finn Slough is a vibrant artist community and a unique heritage village on Richmond’s outskirts.

Despite historical anti-immigrant sentiments, many immigrant groups established themselves in Steveston. After completing the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1885, hundreds of Chinese workers supported the rapid expansion of canneries on British Columbia’s coast. While most did not fish, they worked in fish processing, soldered can lids, and operated retort ovens.

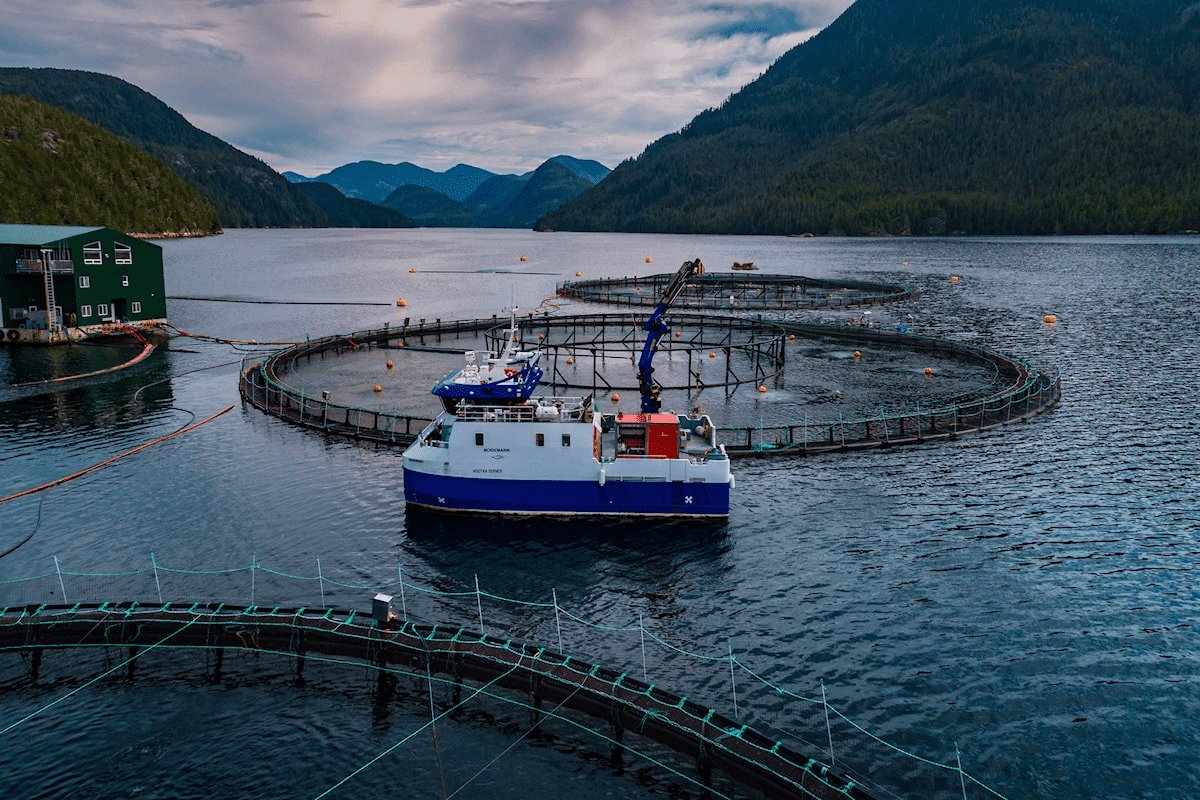

Fishing and Aquaculture in Vancouver

In Vancouver, fishing and aquaculture are integral to daily life, blending commercial and recreational activities. The city’s pristine bays and excellent water quality make it an ideal haven for anglers and aquaculture enthusiasts.

The region is home to diverse marine species, with salmon, shellfish, and sea plants being the most abundant. Commercial fishing yields salmon, herring, bottom fish, and shellfish, while recreational fishing offers peaceful outdoor experiences.

Fishing After World War I

Following World War I, the demand for jobs from veterans ended limited licensing restrictions for salmon fishing, at least for white individuals. However, restrictions remained for Indigenous and Japanese Canadians, while white fishers gained dominance.

During this period, the use of gillnets persisted, and the purse seine and troll fisheries grew. By the late 1920s, the salmon industry, once boasting over 70 canneries, began consolidating. Sardine fishing, suitable for purse seining and reduction fishing (turning fish into fertilizer or meal), also emerged.

Post-War Technological Advancements

After World War II, fishing fleets adopted new technologies, including radios, radar, sonar, nylon nets, and hydraulic equipment. More powerful vessels enabled larger catches and extended transport distances.

The federal government supported this growth by subsidizing new vessel construction and offering unemployment insurance for self-employed fishers. Initiatives like the Fishermen’s Price Support Board (1947) and vessel loans and insurance in the 1950s further bolstered the industry.

Advocacy and Conservation

Organizations like the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union (UFAWU) played a pivotal role in fisheries management. UFAWU advocated for licensing controls to enhance conservation and income prospects, leading to significant changes in the late 1960s.

By the mid-20th century, British Columbia’s fleet had become more independent, and the salmon canning industry continued to grow. Centered around salmon, herring, and halibut, the province’s fishing industry remains a cornerstone of Vancouver’s economy and culture.