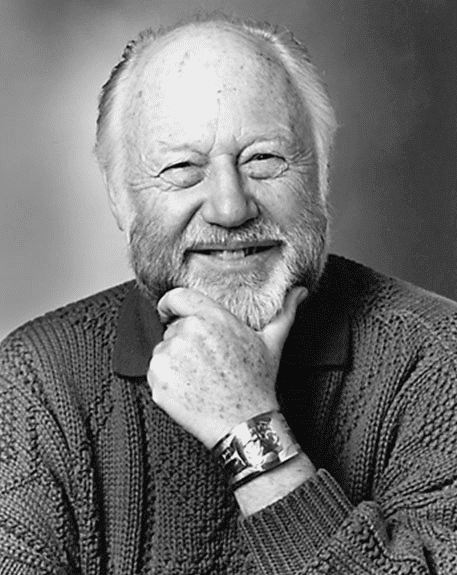

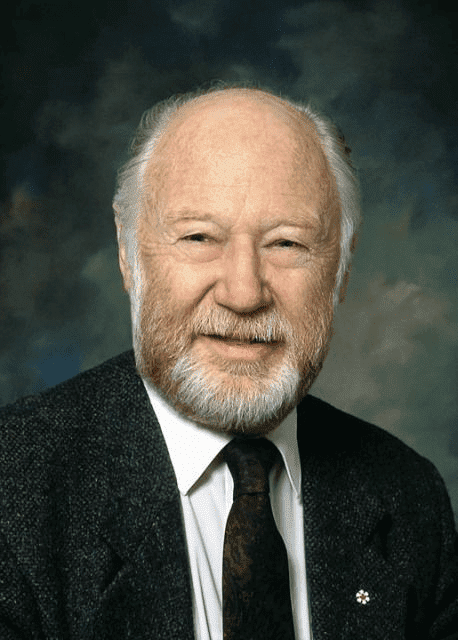

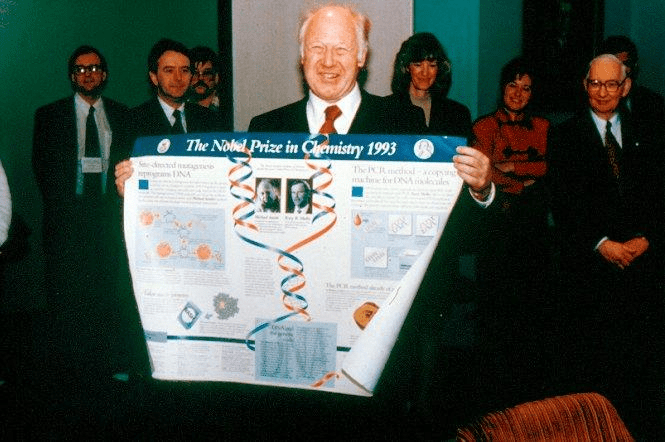

Michael Smith, the 1993 Nobel Prize laureate in Chemistry, passed away at the age of 68. He was a biologist who developed one of the most fundamental methods used in genetic engineering. This method allowed for the reprogramming of genetic codes by replacing the nucleotide molecules that compose them. Michael Smith’s research explored ways to modify genetic material by rearranging the building blocks of DNA in a way similar to rearranging chemical structures with tweezers. Next on vancouver-name.

Childhood, Inspiring Teacher, and Education

Michael Smith, a gifted biologist, was born in Blackpool on April 26, 1932. His parents were working-class; his father, Rowland, was an avid gardener specializing in chrysanthemums, while his mother, Mary Agnes, managed a guest house. She was a devout churchgoer who sent young Michael to Sunday school weekly.

At 11, Smith earned a scholarship to attend the private Arnold School, where his chemistry teacher, Mr. Law, became a significant influence. Mr. Law encouraged his students to broaden their knowledge and perspectives, even suggesting they read newspapers outside their household subscriptions. This led Michael to become a lifelong reader of the Manchester Guardian. His appreciation for structure and learning grew further as he discovered The New Yorker, which became another lifelong favourite source of information.

In 1950, Smith enrolled at the University of Manchester to study chemistry. He earned his PhD in 1956. During his final year, he and his peers applied for jobs in America. In the summer of 1956, Smith learned about Gobind Khorana, a brilliant young scientist at the British Columbia Research Council in Vancouver, who had a research assistant position available. The role involved developing methods to synthesize molecules belonging to biologically significant organophosphate groups.

Early Career and Research

In 1957, Michael Smith began an exciting new chapter in his career. The chemistry he encountered was significantly more complex than the compounds he had studied during his doctoral research. However, this challenge pushed him to conduct deeper studies into newly discovered substances of great biological significance.

In 1960, Smith joined Khorana’s group when it moved to the Institute for Enzyme Research at the University of Wisconsin. There, they tackled what Smith described as one of the most challenging problems for nucleic acid chemists—the synthesis of ribooligonucleotides.

By 1961, Smith returned to Vancouver, full of inspiration and ready to embark on groundbreaking discoveries. He immediately began exploring the complexities of nucleic acids at the Fisheries Research Board of Canada Laboratory. In 1966, Smith joined the Canadian Medical Research Council, setting the stage for his Nobel Prize-winning work.

In 1986, Smith transitioned from Cambridge’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology to Yale University before founding the Biotechnology Laboratory in Vancouver, a move that significantly enhanced the city’s reputation in the global scientific community.

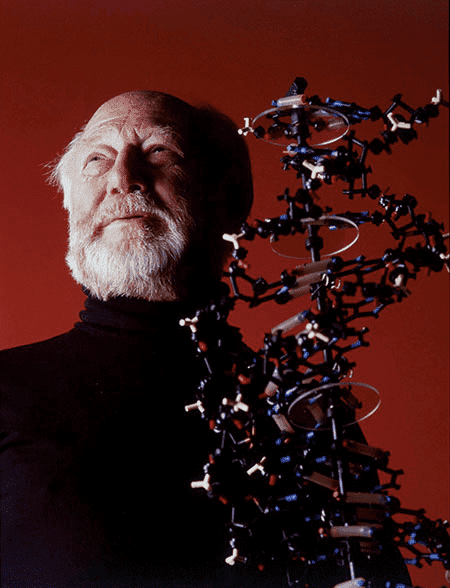

DNA: More Than a Genetic Instruction Manual

For Smith, science was not merely about finding answers to specific questions but about exploring the unknown. To him, uncovering how genetic codes function was akin to embarking on an adventurous quest, where every corner could hide an incredible secret.

His realization that DNA is not just a genetic blueprint but also a key to protein synthesis astonished both the scientific community and the world. By studying oligonucleotides and their interactions with viral DNA, he discovered that even minor changes could lead to significant outcomes in creating new DNA.

A pivotal moment came during a coffee break in Cambridge, when the idea emerged to link a reprogrammed synthetic oligonucleotide with a DNA molecule and replicate it in a host organism. This concept, realized in 1978, allowed Smith and his team to induce mutations in viruses and “cure” natural mutants by restoring their original properties.

In 1997, Smith left academia to become the director of the Genome Sequencing Centre at the Cancer Agency in Vancouver. Earlier, in 1981, he co-founded the biotech company Zymos with Ben Hall and Earl Dawe. Their collaboration with Novo Nordisk led to the development of a yeast-based process for producing human insulin, further cementing Smith’s legacy in biotechnology.

Personal Life and Legacy

Smith’s love for nature and Vancouver’s rugged beauty deeply influenced his personal and professional life. In 1960, he married Helen Christie, a Vancouver native, with whom he had three children: Tom, Ian, and Wendy. After becoming a Canadian citizen in 1963, he joined the University of British Columbia (UBC) as an assistant professor. He was promoted to full professor six years later and secured numerous grants for foundational research, culminating in his Nobel Prize in 1993.

Smith used the $500,000 Nobel Prize grant to support initiatives promoting women in science and schizophrenia research. His groundbreaking work continues to revolutionize biotechnology and genetic research, paving the way for future innovations.

Smith’s contributions not only solidified Vancouver’s reputation as a scientific hub but also enhanced Canada’s standing in global scientific advancements. His enduring legacy remains a testament to his dedication, vision, and profound impact on the scientific world.