Squat concrete warehouses, protected by barbed wire fences and steel mesh windows, stretch into the morning light. The area appears desolate, with dust covering windows and sills, and trash littering the alleyways. In the doorway of one of the many run-down buildings, a group of disheveled men gathers to trade drugs. Next on vancouver-name.

Further down the alley, nestled between a budget hotel and a poultry processing plant, a trio of young artists paints canvases in studios located in the lofts and workshops of a repurposed sugar factory towering over the street. A rain-soaked sex worker stands on the corner, while a dozen immigrant women huddle from the downpour, waiting for a bus to take them home after a grueling day of work in sweatshops.

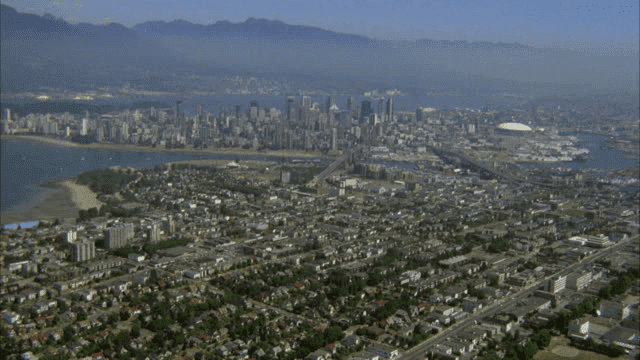

On the main boulevard, a ceaseless stream of vehicles rushes by, transporting passengers from their downtown condominiums to suburban jobs in office complexes, industrial parks, and sprawling retail centres.

This is the recent reality of Vancouver.

Vancouver’s Industry: The Reality from 1997 to 2007

For years, Vancouver’s politicians and urban planners, enamoured with high-rise living and the sleek downtown lifestyle—not to mention the praises sung by condominium developers—neglected the industrial needs of the city. By 2007, the availability of vacant industrial land in the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) had dropped by nearly 50 percent over the past decade. Within Vancouver itself, 600 hectares had been lost, leaving the city with only about 36 hectares of undeveloped land designated for industrial purposes.

Declining Industrial Land

Some of this vacant land was situated along the Fraser River on the city’s southern boundary, but much more lay east of False Creek on former railway lands once earmarked for a high-tech hub. These lands, left in limbo, became a patchwork of urban factories, furniture outlets, and warehousing companies. Another industrial area around Mount Pleasant had been repurposed into a mix of offices, retail spaces, and workspaces. Developers, anticipating the city’s abandonment of Mount Pleasant’s industrial designation, aggressively acquired properties, flipping them to prepare for future townhouse developments—pricing out small industrial businesses. Meanwhile, in Strathcona, Vancouver’s original industrial zone, less than half a hectare of vacant industrial land remained along Powell Street, with slightly over a hectare near Clark Drive.

Vancouver Without Industrial Growth

Vancouver, at the dawn of the 21st century, could not thrive solely on condos and office towers. The city needed to make room for both “blue-collar” and “new-collar” jobs—traditional services ranging from auto repair shops to print shops and modern clean industries like film production, IT, and biotechnology. Strategically grouped spaces were necessary for next-generation industries that would provide jobs and revenue for decades to come. These spaces needed to be close to the downtown core, with transportation routes ensuring the efficient and clean movement of goods, services, and people.

But the reality was grim: Vancouver lacked a coherent strategy to retain and attract industry, while its industrial lands were disappearing. A GVRD inventory revealed that between 1996 and 2005, the region’s supply of vacant industrial land halved from 4,600 hectares in 1996 to 2,800 hectares in 2005. This scarcity also pushed up lease rates for developed industrial properties. A CB Richard Ellis Ltd. regional survey in late 2006 noted that between 2003 and the end of 2006, the vacancy rate for industrial rental buildings fell from 3.5 percent to 1.7 percent. Prospective buyers faced hostile zoning regulations, uncooperative environments, and property owners holding out for residential developers.

Strathcona: A Neglected Industrial District

Except for its traffic flow—20,000 vehicles used Powell Street daily as a conduit to the downtown core—Strathcona was emblematic of Vancouver’s neglected industrial reality. This roughly 10-block stretch of East Vancouver extended from the infamous Downtown Eastside to Clark Drive, bordered by fenced-off port areas and vibrant wooden houses in the historic, low-income residential district of Strathcona, home to many Chinese immigrants. It was one of the city’s few areas still supporting light manufacturing, distribution, and repair businesses. By 2007, it provided at least 8,000 jobs across approximately 300 small firms—one-quarter of Vancouver’s manufacturing jobs and half of its warehouse positions.

The majority of these firms employed fewer than six workers. Industrial jobs dwindled as manufacturers vacated the area, leaving buildings to decay. Some structures were repurposed as low-rent offices for social agencies grappling with the Downtown Eastside’s overwhelming homelessness crisis. Despite being officially protected as an industrial zone, Strathcona had been mistreated for decades, used as a dumping ground for governmental social failures. The result was a steady erosion of blue-collar industrial jobs.

A Lack of Suitable Industrial Space

Vancouver wasn’t alone in its industrial land shortage. The entire Lower Mainland was waking up to how little space remained for industrial development. GVRD studies indicated that at least 120 hectares of industrial land were being lost annually. While the region technically still had 2,800 hectares zoned as vacant industrial land, half of that was already occupied by housing or subject to environmental or other restrictions. Many of these plots were poorly located, far from communities, businesses, and transportation routes. Over 80 percent of the region’s remaining industrial land was south of the Fraser River.

This posed a challenge for Vancouver. By 2007, “industry” no longer meant sprawling, smoke-belching factories. Instead, it referred to clean, quiet service sectors like computer system design and new media. It also included logistics operations like warehouses and trucking facilities. Yet vacancy rates for functioning factories and warehouses in Vancouver were below one percent. Entire blocks of empty buildings in Strathcona were destined for demolition rather than repurposing.

Vancouver: A Business Hub Without Prosperity Strategies

Unusually among major cities, Vancouver was considered a key regional hub for business and employment, accounting for 28 percent of the region’s population, 35 percent of its jobs, and 36 percent of its businesses. However, it lacked strategies to sustain its prosperity. The city had no vision for future opportunities and showed little coordination between governments and industries. Its industrial zones were traditionally overlooked, with officials seemingly assuming there would always be more land available.

One notable example was the Entwistle Agency, which operated out of bright, glassy offices on the 16th floor of a tower on West Georgia Street, near Strathcona. The agency conducted a significant three-year study to identify global-scale industrial niches Vancouver could fill. Entwistle cited a prominent new media company, akin to Electronic Arts Inc., which considered building a 500-employee facility in Vancouver. Ultimately, the firm abandoned the idea because it couldn’t find suitable industrial land or other collaborative incentives.