Every city eventually faces the challenge of providing its residents with sufficient fresh water. However, this has always been a significant problem for Vancouver. This is a common drawback of cities located near the sea. While Vancouver’s modern sanitation services resemble those of other cities with saline water systems, its path to achieving this was relatively straightforward and less costly. Below vancouver-name, we explore how the city’s water supply system operates today and delve into Vancouver’s historical journey.

How Does the Water Supply and Sewer System Work?

Vancouver boasts 1,450 km of water mains and 2,800 km of sewer pipes.

This intricate network delivers 295 million litres of fresh drinking water daily to homes and businesses while removing excess water and sewage for treatment. Additionally, the city incorporates cutting-edge ecological research to design systems that collect rain and stormwater from buildings, roads, and parking lots. These systems direct the water into local waterways like Burrard Inlet and the Fraser River.

To avoid costly mega-projects, Vancouver conducts annual sewer replacements and maintenance. This ensures the city significantly extends the lifespan of its sewer pipes, which deteriorate over time due to soil conditions and age. Typically, underground sewer mains last about 100 years.

Looking to the future, Vancouver is working to enhance its ecological impact. By 2050, the city aims to replace all combined sewer systems with separate ones in every building. This shift will prevent untreated sewage from entering waterways.

Before starting construction in any area, residents receive a notification from city officials outlining the project schedule and other details. Construction crews dig trenches for water mains or sewers to install new pipes. These activities involve heavy road traffic, equipment, and potential parking restrictions or road closures. Once the pipework is complete, streets, boulevards, and sidewalks are restored. These final restoration tasks might occur sometime after the trenches are filled and temporarily patched.

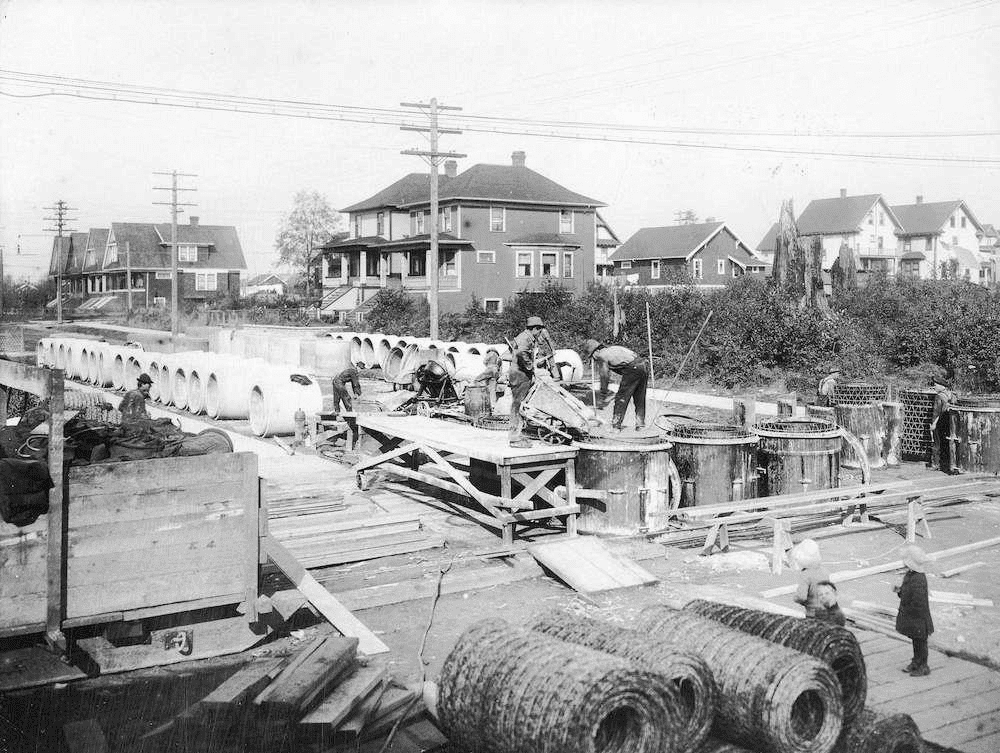

Vancouver’s Sewer System in the 19th Century

In 1887, Vancouver lacked most urban services. Water supply and sanitation practices mirrored those of rural areas: water was drawn from shallow underground wells, and wastewater was discharged onto the ground. The sandy soil quickly allowed decomposing wastewater to seep into groundwater, contaminating the water supply. This led to outbreaks of cholera, typhoid fever, and other diarrheal diseases.

Vancouver’s residents recognized that a safe water supply could reduce typhoid cases. However, efforts to maintain water supply and sewer systems often resulted in damage, leading to occasional but destructive fires.

In the short term, the city constructed underground water reservoirs holding 50,000 gallons each to combat fires. In the long term, the threat of fire bolstered arguments for developing robust water supply and sewer systems.

Sewer Development and Initial Challenges

The Vancouver City Council laid the sewer system while constructing streets. By the end of 1888, sewers discharged into Burrard Inlet and False Creek. Although the sewer design aligned with contemporary engineering practices, initial efforts were problematic due to insufficient water flow from emergency reservoirs, preventing proper system flushing.

A new system completed the following year resolved these issues, marking a turning point in Vancouver’s infrastructure development.

This early investment in water supply and sewer systems not only addressed immediate public health concerns but also laid the groundwork for the city’s rapid growth and modernization.

Competition Between Vancouver Water Works and Coquitlam Water

The Vancouver Water Works Company was established in 1886 by J. Keefer and O. Smith under an act of the provincial legislature. These two individuals were part of a group that held franchises for several other urban services, including electricity, gas, and transit.

During the winter of 1885-86, Keefer organized a survey, led by Henry Smith, of all streams flowing into Burrard Inlet. Smith’s team recommended using the Capilano River as Vancouver’s water source. The decision was based on the river’s higher water flow, proximity to the city, and steep gradient, which allowed for a gravity-fed water supply from an intake point upstream. The company’s initial capital was $250,000, designated for delivering water from the Capilano River to Vancouver.

Before obtaining the franchise, Vancouver Water Works faced competition from Coquitlam Water, another company registered by the provincial legislature. Coquitlam Water planned to supply New Westminster with water from Coquitlam Lake and also aimed to serve Vancouver. On April 25, 1887, the city council narrowly voted to accept Coquitlam Water. However, when the issue was put to voters on June 5, 1888, they rejected the public charter granting ownership to the Coquitlam group.

The reasons for rejecting the charter were debated later, but ultimately, Vancouver had to negotiate with Vancouver Water Works Co. Construction began immediately after the deal. In the summer of 1886, Keefer’s group conducted detailed studies to determine the water intake point and crossing location for Burrard Inlet.

Modern Water Supply Systems in Vancouver

Today, Vancouver’s water is collected from the Capilano, Seymour, and Coquitlam reservoirs. On average, the city’s water system delivers 360 million litres of high-quality water daily.

As Vancouver’s population has steadily grown over the years, so has the volume of wastewater produced. Each year, Metro Vancouver treats approximately 440 billion litres of wastewater from households, industries, and stormwater runoff. This wastewater travels through an extensive network of pipes and sewers to one of Metro Vancouver’s five treatment facilities:

- Iona Island Wastewater Treatment Plant (Richmond)

- Lulu Island Wastewater Treatment Plant (Richmond)

- Annacis Island Wastewater Treatment Plant (Delta)

- Lions Gate Wastewater Treatment Plant (West Vancouver)

- Northwest Langley Wastewater Treatment Plant (Langley)

Wastewater Treatment and Environmental Concerns

Four of these facilities use primary and secondary treatment methods. The oldest facility, Iona Island, employs the simplest and oldest technology, releasing treated wastewater into the environmentally sensitive Georgia Strait, where the Fraser River empties.

Recognizing the environmental risks, Vancouver has launched a modernization program for Iona Island’s treatment facility. By 2030, the facility will include both primary and secondary treatment methods. This upgrade is critical to reducing harmful pathogens in untreated wastewater that can cause disease upon contact or ingestion.

Modern wastewater treatment protects public health and the quality of water in surrounding lakes and rivers. Vancouver’s system uses a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes to remove pollutants. However, this system is energy-intensive and costly, underscoring the need for residents to minimize water consumption and properly dispose of hazardous household waste.

A Historical Perspective

The history of Vancouver’s water and wastewater systems reflects the city’s early challenges in managing urban services. Competition between Vancouver Water Works and Coquitlam Water marked the beginning of Vancouver’s journey toward securing a reliable water supply.

From those early days of relying on a single source, Vancouver now benefits from advanced systems that serve a growing population while striving to protect the environment.